Installation view of "Josh Smith" at Luhring Augustine. Photos: 16 Miles [more]

Installation view of "Josh Smith" at Luhring Augustine. Photos: 16 Miles [more] Installation view of "Josh Smith" at Luhring Augustine, New York

Installation view of "Josh Smith" at Luhring Augustine, New YorkNot so long ago,

Josh Smith was one of the most divisive artists in town, a rare figure whose work could provoke fights between friends with otherwise likeminded views on contemporary art. I was among the skeptical. His art seemed to me indulgent and lazy, all of those

giant fish,

leaves, and

signatures accumulating in an unending, unedited stream. His success seemed to herald the emergence of a new band of what

Peter Schjeldahl, in the 1980s, dubbed

“the new dumb painters.”Schjedahl placed

Julian Schnabel,

Sandro Chia, and

George Condo in that camp, and, in

a review of the latter, argued that they “bet that their own innocent pleasure in painting proves that painting (and they) will be immortal.” Pleasure and immortality: I cannot think of better words with which to characterize Smith’s interests, particularly in the numerous works in which he

spells his name with thick, generous waves of color. Those words certainly apply to the pieces in his most recent show,

at Luhring Augustine. Smith, of course, does not paint like those artists (though it is tempting to see some of Schnabel’s bravado in the raw confidence he projects in his art). Rather, I think that his twin forebears — indulge me here for a second — are

Jasper Johns and

Martin Kippenberger.

Like Johns, Smith is interested in the symbolic order of things. But, instead of flags, numbers, and targets, he paints

the letters that signify his name or those that convey the

information for his shows. When he paints objects — those

leaves,

fish, and in his current show,

skeletons — they are always enlarged to fit the size of the canvas and outlined with multiple streams of color. You could not mistake them for a physical thing in the world: they are instead foundational symbols for objects, ideas of what leaves or fishes or skeletons are.

Installation view of "Josh Smith" at Luhring Augustine, New York

Installation view of "Josh Smith" at Luhring Augustine, New York Josh Smith, Untitled, 2010. Mixed media on panel (12 panels), 144 x 144 in.

Josh Smith, Untitled, 2010. Mixed media on panel (12 panels), 144 x 144 in.These objects are also enablers, maybe even excuses, for Smith’s painting, filling the same role in his practice that the egg did in Martin Kippenberger’s. (“In painting you must look what fallen fruit is left that you can paint,”

Kippenberger said. “The egg has missed out there,

Warhol already had the banana.”) They allow Smith to get to work, to start spreading paint around the canvas, to really let it rip. Which is great, because when he really gets going, as he does frequently here, he makes thrilling art, rich with ideas and, yes, filled with layers and layers of visual pleasure. His subjects appear again and again, but they’re presented anew each time, fresh and bizarre.

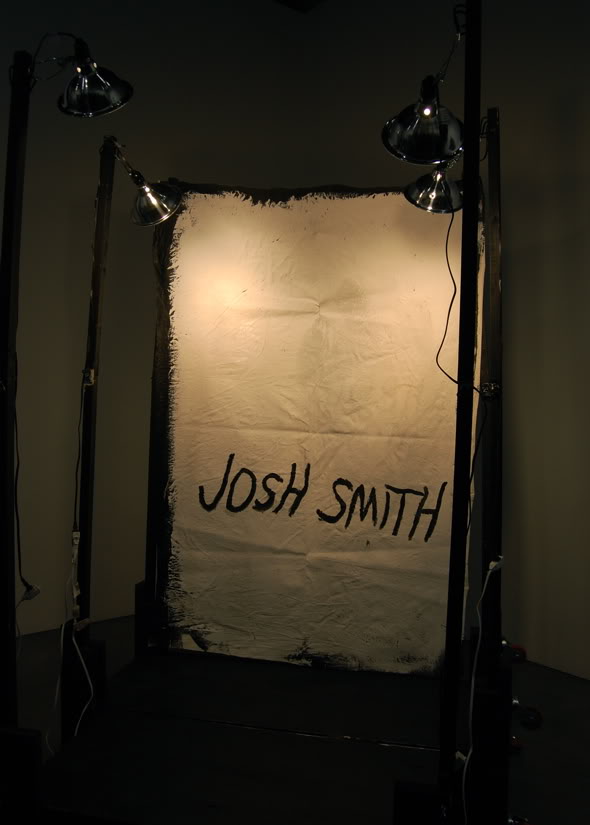

Smith’s two major innovations here also channel Johns and Kippenberger. There are red stop signs painted on squares of aluminum, another symbolic product of culture that parallels Johns’ flag. In at least one corner of each there is a dash of paint or a handprint — always some expressive touch — to differentiate them, to keep Smith in the picture. And then there are the

Stage Paintings, rickety wood platforms fitted with lights that are pointed to a sheet of canvas painted with his name. The artist is up on stage, dead center, in front of the lights and performing for the crowd. (

“Dear Painter, paint for me!”) I suspect that their wit would have impressed Kippenberger; this comment, made by Smith in a recent Art in America interview, certainly would have: “I don't think I've ever made the same thing twice. I have never given myself the luxury.” Is there an ascetic hiding behind all those paintings?

Smith has big projects ahead. He’s creating a site-specific installation at the

Brant Foundation and has been tapped by

Bice Curiger for her Venice Biennale exhibition. As curatorial consensus solidifies around him, he’s responding with admirable ambition, painting larger works — some filling six or a dozen panels — and expanding his array of options. So far, the results are explosive. Just how dramatically can he scale his work without it losing its punch? All signs suggest that he will be here for the long haul, but we’ll soon know for certain. If it does work out — and again, I suspect it will — I hope for installations that are even more elaborate and peculiar. The

Stage Paintings could be just the beginning: in future shows I imagine boxing rings, tight-rope assemblies, and three-ring circuses, all draped with canvases bearing two giant words: JOSH SMITH.

Josh Smith, Untitled, 2010. Mixed media on panel, 48 x 36 in.

Josh Smith, Untitled, 2010. Mixed media on panel, 48 x 36 in. Detail view of Josh Smith, Untitled, 2010. Mixed media on panel (12 panels), 144 x 144 in.

Detail view of Josh Smith, Untitled, 2010. Mixed media on panel (12 panels), 144 x 144 in. Josh Smith, Stage Painting 1, 2011. Wood, paint, fabric, lights, and hardware, 96 x 68 x 54 in.

Josh Smith, Stage Painting 1, 2011. Wood, paint, fabric, lights, and hardware, 96 x 68 x 54 in. Josh Smith, Untitled, 2010. Enamel on aluminum, 48 x 48 in.Previously: Josh Smith, "On the Water," at Deitch Studios, Long Island City, May 25, 2010

Josh Smith, Untitled, 2010. Enamel on aluminum, 48 x 48 in.Previously: Josh Smith, "On the Water," at Deitch Studios, Long Island City, May 25, 2010