New York! Last January, I moved back here from South Korea, and so my top 10 list for 2024 is focused largely on the city, with some other shows I visited while traveling also in the mix. I had almost (but not quite) forgotten just how art-rich New York is. Whether measuring by quantity or quality, there is no place like it, and so assembling a top 10 was difficult. But I managed. It follows below. Before that, though, here are a few other exhibitions (plus a performance and a television show) that have stuck with me from the past 12 months:

Anicka Yi's potent retrospective at the Leeum in Seoul, as well as the museum's "Dream Screen" exhibition of young Korean artists, curated by Rirkrit Tiravanija, with one of the most unusual exhibition designs I have ever seen; a trio of Jacob Kassay outings, at Mr. Fahrenheit, an empty apartment in Brooklyn Heights, and 303; the glorious "Edges of Ailey" at the Whitney Museum; William Kentridge's The Great Yes, The Great No (2024) opera at the Adrienne Arsht Center for the Performing Arts in Miami; Peter Doig's majestic "The Street" show at Gagosian; Nathan Fielder and Benny Safdie's awfully of-the-moment The Curse, which began in 2023 but ended in January; Galleria Mattia De Luca's Giorgio Morandi blowout on the Upper East Side; Park Seo-Bo's enigmatic and moving final works at White Cube; Nate Boyce's shapeshifting video in a pitch-black Lomex; Hung Liu at Ryan Lee; Darcy Morelos at Dia in Chelsea (which opened in 2023); Nolan Simon at the new 47 Canal; the masterpiece-heavy "Enchanted Reverie: Klee and Calder" at Di Donna Galleries; John Duff at Reena Spaulings; the touring "Martin Wong: Malicious Mischief" at the Stedelijk; the melancholy Rudolf Stingel installation at Gagosian; Diane Simpson at James Cohan; "Bill Traylor: Works from the William Louis-Dreyfus Foundation" at David Zwirner; Win McCarthy at Francis Irv; the Francis Picabia feast (all portraits of women) at Michael Werner; Lee Shinja at Tina Kim; "Make Way for Berthe Weill" at the rechristened Gray Art Museum; Anna Rubin at Essex Street; "Arshile Gorky: New York City" at Hauser & Wirth (not least for its sumptuous foldout poster showing the artist's old haunts); Daniel Pommereulle at Ramiken; and last but not least, the old-school and not-unrelated Greene Naftali outings by two stalwarts, Michael Krebber and John Knight.

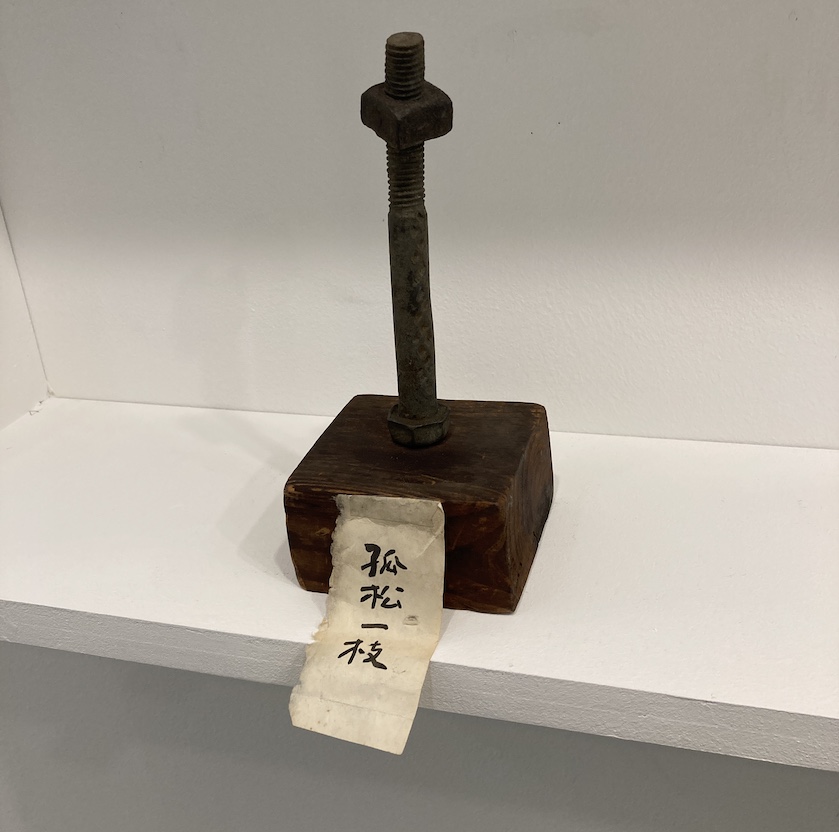

Installation view of “Shinkichi Tajiri: The Restless Wanderer” at the Bonnefanten Museum in Maastricht, the Netherlands.

Installation view of “Shinkichi Tajiri: The Restless Wanderer” at the Bonnefanten Museum in Maastricht, the Netherlands.

10. “Shinkichi Tajiri: The Restless Wanderer” at the Bonnefanten Museum, Maastricht, the Netherlands

Revelatory. Shinkichi Tajiri was born in Los Angeles in 1923, was interned during World War II as a Japanese American, fought in Europe, and faced discrimination when he returned home, so he decided to settle in the Netherlands, where he died in 2009 at 85. He was a winningly restless sculptor, almost too inventive, as this retrospective, curated by his grandchildren, Tanéa and Shakuru Tajiri, showed. (The market has trouble with multifarious figures; historians sometimes do, as well.) His creations included wild robots, ambitious biomorphic abstractions (some based on knots have an alluring tension), and sci-fi–inflected, machine-like figures. Charm and menace commingle. This is a thoroughly honest art: in awe of the world and human creativity, and a bit wary of them, too.

Installation view of “Monte di Pietà: A Project by Christoph Büchel” at the Prada Foundation in Venice.

Installation view of “Monte di Pietà: A Project by Christoph Büchel” at the Prada Foundation in Venice.

9. “Monte di Pietà: A Project by Christoph Büchel” at the Prada Foundation, Venice

When Christoph Büchel is at his best, he's peerless in the realm of mind-bending institutional critique, and when he's not, the results can be baleful. At the Prada Foundation, he was in top form, filling its palazzo with all manner of junk, obscure treasure, gambling equipment, and a lot more—a display that apparently referenced the monte di pietà (a "mount of piety," a charitable pawnshop) that operated on the site from 1834 to 1969. Furtive and powerful flows of money, energy, and history seemed to flow through the building. The operators of this multilayered capitalist fantasia were nowhere to be found, but you could sense that they were watching.

Installation view of Donna Dennis’s Deep Station (1981–85) at the Ranch in Montauk, New York.

Installation view of Donna Dennis’s Deep Station (1981–85) at the Ranch in Montauk, New York.

8. “Donna Dennis: Deep Station” at the Ranch, Montauk, N.Y.

Installation view of Thomas Hirschhorn’s Fake it, Fake it–till you Fake it (2023) at Gladstone in New York.

Installation view of Thomas Hirschhorn’s Fake it, Fake it–till you Fake it (2023) at Gladstone in New York.

7. “Thomas Hirschhorn: Fake it, Fake it–till you Fake it” at Gladstone Gallery, New York

Remember when Chelsea galleries were filled with ambitious, bizarre, and discomfiting installations like this? At the time, it could be exhausting. But now I miss those days. In a year of polite, safer-than-usual shows in Chelsea, Thomas Hirschhorn brandished his trademark cardboard and duct tape to create a frankly oppressive environment that was part Apple store, part digital war zone, part social-media hellscape. Like Büchel's Venice tour de force, it was at once au courant and outmoded—an art struggling gamely to grasp the full horror of the present.

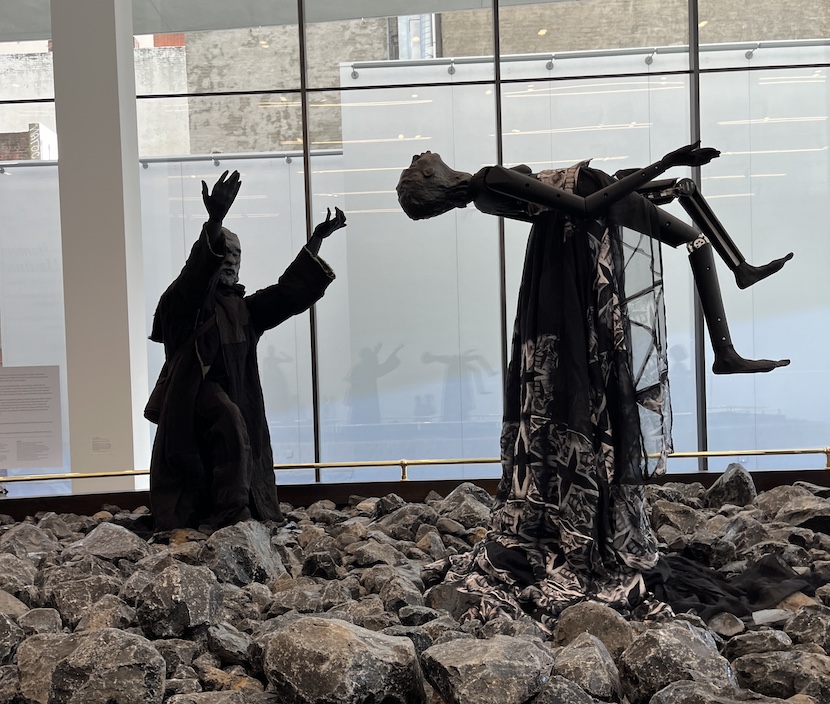

Installation view of Kara Walker’s Fortuna and the Immortality Garden (Machine), 2024, at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Installation view of Kara Walker’s Fortuna and the Immortality Garden (Machine), 2024, at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

6. “Kara Walker: Fortuna and the Immortality Garden (Machine)” at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

It is a wonderful and wise thing that Kara Walker's kinetic installation Fortuna and the Immortality Garden (Machine)... (only part of its long, evocative title) will be on view at SFMOMA into 2026: It offers a lot, and one could learn a lot from repeat visits, I suspect. Black automatons stand in a rock-filled landscape as rituals and quotidian acts transpire. A woman floats magically into the air as a kind of spiritual leader appears to guide her with his hands. A girl cradles a doll. A solitary woman emits printed fortunes from her mouth (it was not working when I was there, but it was impressive nonetheless). Plush seating around the edge of the main installation suggests a grand old museum or an opera house. Disparate worlds and histories are coming together. It's addressing America today—deep time, too.

Anh-Phuong Nguyen's SilkAirways_GirlStandee_New.png (2024) in “Means of Production” at the Sheerly Touch-Ya and Shiwansu warehouse in Queens

Anh-Phuong Nguyen's SilkAirways_GirlStandee_New.png (2024) in “Means of Production” at the Sheerly Touch-Ya and Shiwansu warehouse in Queens

5. “Means of Production” at Sheerly Touch-Ya and Shiwansu, Queens

Simone Martini’s ca. 1340 Christ on the Cross in “Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300–1350” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York

Simone Martini’s ca. 1340 Christ on the Cross in “Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300–1350” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York

2. “Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300–1350” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Masterpieces marshaled from august museums and assembled in high style: This is why you live in New York.

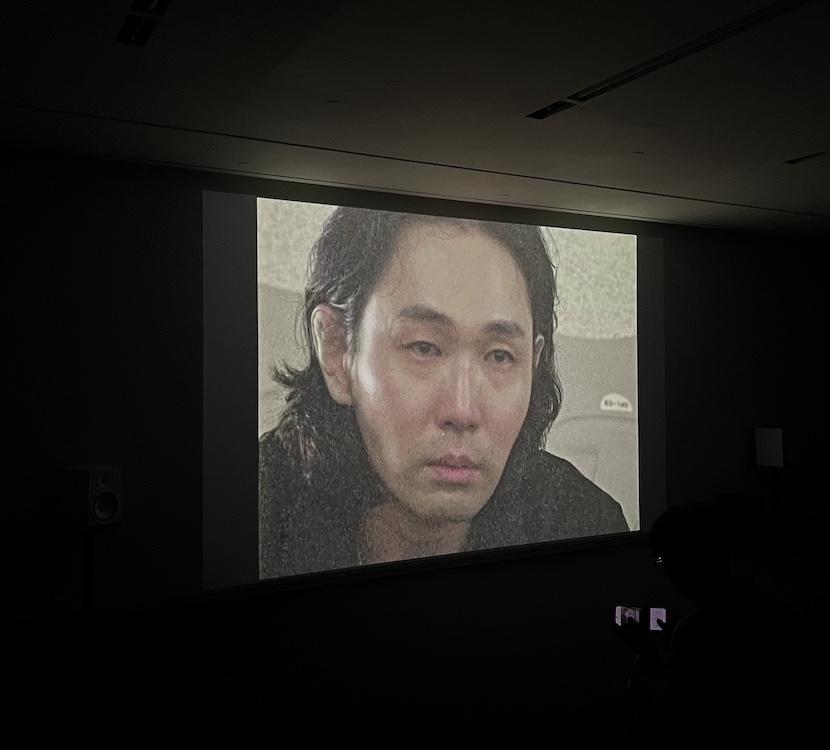

Heecheon Kim’s video Studies (2024) on view at the Atelier Hermès in Seoul

Heecheon Kim’s video Studies (2024) on view at the Atelier Hermès in Seoul

10. “Shinkichi Tajiri: The Restless Wanderer” at the Bonnefanten Museum, Maastricht, the Netherlands

Revelatory. Shinkichi Tajiri was born in Los Angeles in 1923, was interned during World War II as a Japanese American, fought in Europe, and faced discrimination when he returned home, so he decided to settle in the Netherlands, where he died in 2009 at 85. He was a winningly restless sculptor, almost too inventive, as this retrospective, curated by his grandchildren, Tanéa and Shakuru Tajiri, showed. (The market has trouble with multifarious figures; historians sometimes do, as well.) His creations included wild robots, ambitious biomorphic abstractions (some based on knots have an alluring tension), and sci-fi–inflected, machine-like figures. Charm and menace commingle. This is a thoroughly honest art: in awe of the world and human creativity, and a bit wary of them, too.

9. “Monte di Pietà: A Project by Christoph Büchel” at the Prada Foundation, Venice

When Christoph Büchel is at his best, he's peerless in the realm of mind-bending institutional critique, and when he's not, the results can be baleful. At the Prada Foundation, he was in top form, filling its palazzo with all manner of junk, obscure treasure, gambling equipment, and a lot more—a display that apparently referenced the monte di pietà (a "mount of piety," a charitable pawnshop) that operated on the site from 1834 to 1969. Furtive and powerful flows of money, energy, and history seemed to flow through the building. The operators of this multilayered capitalist fantasia were nowhere to be found, but you could sense that they were watching.

8. “Donna Dennis: Deep Station” at the Ranch, Montauk, N.Y.

I still can't believe that Donna Dennis's Deep Station (1981–85) is real. It is a massive installation, a scaled-down subway station fashioned from wood, Masonite, paint, glass, metal, and plastic. Every few minutes, through unseen speakers, it emits the sound of a train, which never appears. It has strong connections to art history (George Tooker, Edward Hopper) and psychological states, but it is also one of those are rare artworks that seems to harbor mysteries, that slips away from pat explanations. It is, I wrote in Artnet, "a place of confinement, of refuge, and of thinking. It is in limbo." It is a crime that it has not been purchased by a leading art museum and put on permanent display.

7. “Thomas Hirschhorn: Fake it, Fake it–till you Fake it” at Gladstone Gallery, New York

Remember when Chelsea galleries were filled with ambitious, bizarre, and discomfiting installations like this? At the time, it could be exhausting. But now I miss those days. In a year of polite, safer-than-usual shows in Chelsea, Thomas Hirschhorn brandished his trademark cardboard and duct tape to create a frankly oppressive environment that was part Apple store, part digital war zone, part social-media hellscape. Like Büchel's Venice tour de force, it was at once au courant and outmoded—an art struggling gamely to grasp the full horror of the present.

6. “Kara Walker: Fortuna and the Immortality Garden (Machine)” at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

It is a wonderful and wise thing that Kara Walker's kinetic installation Fortuna and the Immortality Garden (Machine)... (only part of its long, evocative title) will be on view at SFMOMA into 2026: It offers a lot, and one could learn a lot from repeat visits, I suspect. Black automatons stand in a rock-filled landscape as rituals and quotidian acts transpire. A woman floats magically into the air as a kind of spiritual leader appears to guide her with his hands. A girl cradles a doll. A solitary woman emits printed fortunes from her mouth (it was not working when I was there, but it was impressive nonetheless). Plush seating around the edge of the main installation suggests a grand old museum or an opera house. Disparate worlds and histories are coming together. It's addressing America today—deep time, too.

5. “Means of Production” at Sheerly Touch-Ya and Shiwansu, Queens

Hell yes. A collective called Lunch Hour (comprised of Lily Jue Sheng, Do Tuong Linh, and Serena Chang) brought together more than 70 artists, including Anh-Phuong Nguyen, Jacob Kassay, and Becky Kolsrud, in a sprawling warehouse in Glendale, Queens, that is home to Sheerly Touch-Ya hosiery, the art fabricators Shisanwu, and artists' studios. The works were, generally speaking, inventive, sly, smart, and sometimes mournful. It was a show about what can be accomplished together, in communion with art. In Artnet, I wrote, "As the international art market becomes ever more top-heavy, corporate, and unequal, this smart and scrappy production is registering the pervasive discontent—and modeling another approach." Here's hoping for a sequel, soon.

Matthew Barney’s video Drawing Restraint 28 (2024) in “The Bitch” at O’Flaherty’s in New York

Matthew Barney’s video Drawing Restraint 28 (2024) in “The Bitch” at O’Flaherty’s in New York

4. “The Bitch: Matthew Barney and Alex Katz” at O’Flaherty’s, New York

Two grandmasters united at the most consistent, unpredictable gallery in town. The result? Unlike anything I have ever quite seen before, at once ironic, comic, and utterly sincere—a show about a show about a show. "The Bitch." In recent paintings, just orange and white, Alex Katz hikes into some thrillingly uncharted terrain (late de Kooning comes to mind, vaguely). He's onto something new as he edges closer to 100. Matthew Barney's video of Katz at work renders the process of painting as miraculous, fearsome, and quotidian labor. I'm stacking up questionable oxymorons here, but that's only because this show was so good, so bewitching, and so true to life.

Installation view of Pacita Abad at MoMA PS1 in Queens.

Installation view of Pacita Abad at MoMA PS1 in Queens.

4. “The Bitch: Matthew Barney and Alex Katz” at O’Flaherty’s, New York

Two grandmasters united at the most consistent, unpredictable gallery in town. The result? Unlike anything I have ever quite seen before, at once ironic, comic, and utterly sincere—a show about a show about a show. "The Bitch." In recent paintings, just orange and white, Alex Katz hikes into some thrillingly uncharted terrain (late de Kooning comes to mind, vaguely). He's onto something new as he edges closer to 100. Matthew Barney's video of Katz at work renders the process of painting as miraculous, fearsome, and quotidian labor. I'm stacking up questionable oxymorons here, but that's only because this show was so good, so bewitching, and so true to life.

3. Pacita Abad at MoMA PS1, Queens

Pacita Abad's death in 2004, at the age of 58, of lung cancer, cut short the career of one of our era's signal artists. (She'd be turning 80 next year.) Abad still managed to build an astonishingly incisive, multifarious, and most of all, joyous body of work, as this concise traveling retrospective showed. (Its MoMA PS1 outing was organized by Ruba Katrib, the museum's director of curatorial affairs.) I wrote in the New York Times: "Abad’s art evinces a deep reverence, a love, for the world—and for people, for what they make with their hands and for what they treasure."

Pacita Abad's death in 2004, at the age of 58, of lung cancer, cut short the career of one of our era's signal artists. (She'd be turning 80 next year.) Abad still managed to build an astonishingly incisive, multifarious, and most of all, joyous body of work, as this concise traveling retrospective showed. (Its MoMA PS1 outing was organized by Ruba Katrib, the museum's director of curatorial affairs.) I wrote in the New York Times: "Abad’s art evinces a deep reverence, a love, for the world—and for people, for what they make with their hands and for what they treasure."

2. “Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300–1350” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Masterpieces marshaled from august museums and assembled in high style: This is why you live in New York.

1. “Heecheon Kim: Studies” at the Atelier Hermès, Seoul

Kim Heecheon's two-channel video, which was the lone work in his show at the Atelier Hèrmes in Seoul felt new, rich and strange. Masterful. Here's what I wrote for Artnet in December:

Student wrestlers have gone missing, and an investigation is underway, as rumors fill the air. That’s the basic plot of Studies (2024), an enigmatic, genuinely frightening two-channel short film by Heecheon Kim, who is one of South Korea’s best video artists, 35 this year. In the past, Kim has drawn on video games and face-altering apps to produce gimlet-eyed, bracingly contemporary work. In Studies, he toys with the conventions of a far older cultural form, the horror movie, mulling how to shoot a convincing one in an era of ultra-high-res cameras and omnipresent technology. Discussing his approach here would spoil it, but let’s just say this: You watch awful things unfold, even as you can’t quite understand them, and the dread just keeps building.

What a piece to screen in the basement of a luxury emporium!

Sangdon Kim's "Monkey Forest," presented at 2021 Gwangju Biennale, on view in a

Sangdon Kim's "Monkey Forest," presented at 2021 Gwangju Biennale, on view in a