Entrance to the Colección Jumex.

Colección Jumex is located within the factory of the eponymous juice company, a bunker on the edge of Mexico City, accessible only by taxi. Before sliding open the metal walls blocking the entrance, security guards question you and check your identity. It's open only via appointment and walled off from the congested streets of the DF. To put it another way: it would be hard to imagine a white box purer than this. (In our two-hour stay, we saw only two other visitors.)

Ugo Rondinone,

Love Invents Us, 1999, neon, Perspex, transluscent film, aluminum, 310 x 721 x 10 cm.

Above the concrete block walls, a Rondinone sign. Within the walls of corporate Mexico on top of La Fundación Jumex's storage facility, its admixture of sincerity and irony had never seemed so perfect.

Clever, adorable labels with little icons identify each work.

It was a smart presentation of pleasurable favorites with a needlessly incendiary title. Focusing solely on the Swiss artists in the collection, it presented a simple thesis well: the days of nationalist art are long over, washed away by an entrenched globalism, at least within the art markets of Chelsea, Berlin, and London.

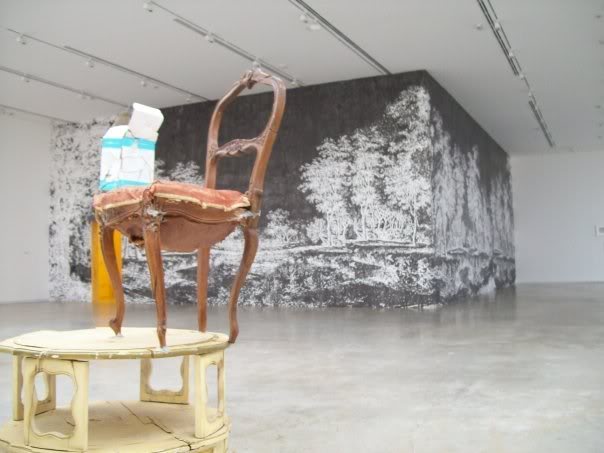

Front: Urs Fischer,

Addict, 2006, mixed media.

Back: Ugo Rondinone,

Where Do We Go from Here?, 1996, ink on wall, playwood, yellow neon, 4 DVDs, 4 projections, 500 x 1200 x 1000 cm.

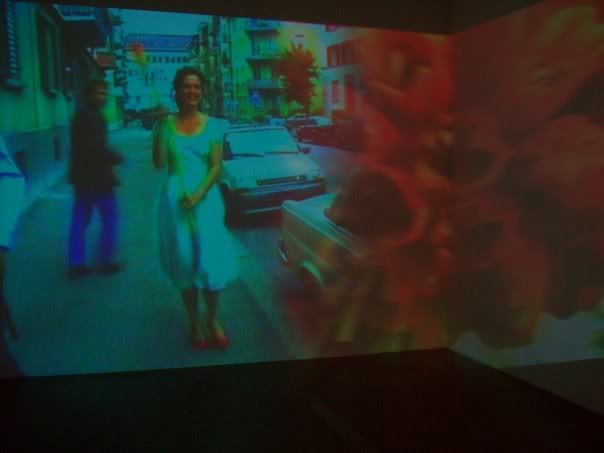

Pipilotti Rist,

Ever Is Over All, 1997, video installation, dimensions variable.

Any exhibition that features Pipilotti Rist's video of a Dorothy-figure wandering down the street, smashing car windows, and smiling to police officers will instantly earn my affection, but there were other charms as well: little icons identifying the art on display and an installation in the offices upstairs by a Mexican artist named Moris, which required you to climb a ladder and jump a wall, dodging barbed wire. Containing tabloids filled with stories of gang violence and organized crime, it injected the reality outside the pristine walls into the center of the collection.

Moris,

Hermoso paisaje No. 5 (el baldio), 2008, installation.

Free, delicious Jumex beverages are available for all visitors.

The real joy, admittedly, had to do with the exclusivity of the affair, viewing art that only a few are likely to see in an environment that - however ridiculous, elitist, and cloistered - would be hard to improve upon. The young employees were tinkering happily with a recently-acquired video work; there were free drinks (Jumex-brand, clearly), a gargantuan research library (in which sat a full set of Artforums, their bindings seductively cascading along the shelves), and a seemingly limitless supply of art (attested to by the stacks of burgundy, catalogue binders filling the offices).